Ultrasound on a chip

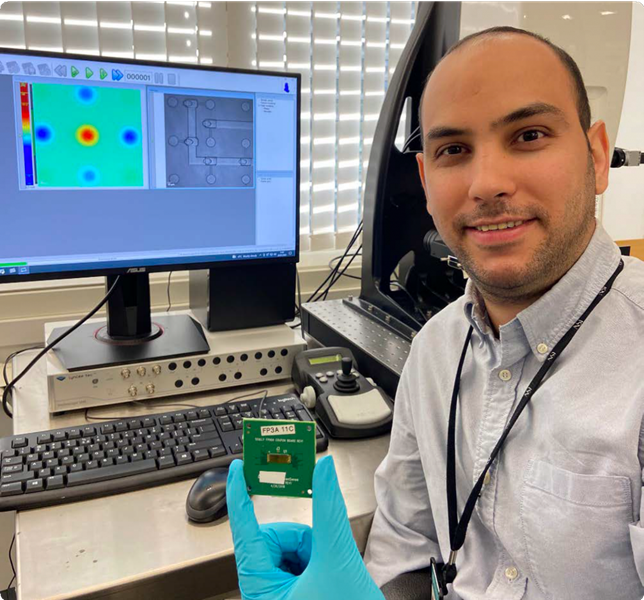

“When you put something on a chip, you are democratising it because it is going to be cheaper and more accessible,” says Amirfereydoon Mansoori. His PhD work aims to contribute to that.

Mansoori is a PhD Candidate at CIUS and part of a research group at the University of South-Eastern Norway (USN) working on the transducer design and manufacturing for various applications, where development of alternative transducer technologies is one of the main activities.

“The production process of the current ultrasound transducers tends to be manual, labour-intensive and expensive. My PhD aims to contribute to modelling, design and characterisation of piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers (PMUTs), which are one alternative to conventional transducers,” says Mansoori.

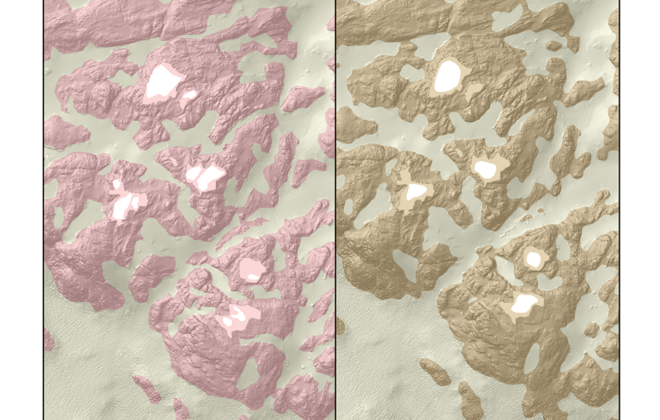

PMUTs are tiny devices. The core of every PMUT is a piezoelectric thin-film, which is typically deposited on a silicon chip based on well-established microelectronic processing techniques. This type of processing offers mass-production that can be much less expensive at large volumes.

The next little thing

PMUTs have been around for some time, but immature processes and low-quality piezoelectric thin-films slowed down the development of high performance PMUTs. “Thanks to remarkable improvements in the piezoelectric thin-film deposition, PMUTs have gained considerable attention in the past 10 years,” says Mansoori.

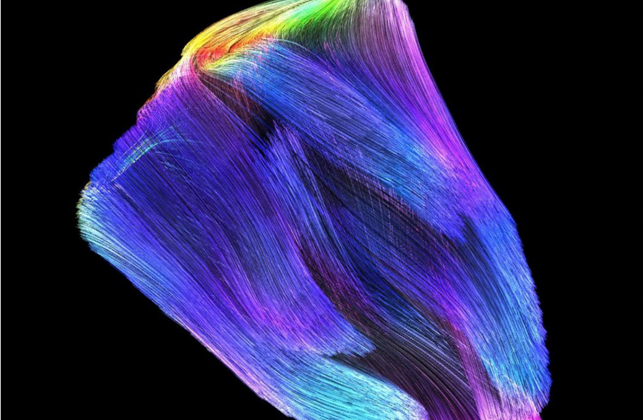

He is in the last year of his PhD and is now concluding his work: “The first part of my project was mostly about identifying the limitations as well as potentials of this new technology through theoretical modelling and simulation. We have also proposed novel design strategies to overcome the limitations and optimise PMUTs for new applications like multi-frequency ultrasound.”

Currently he is working on validating and testing the fabricated PMUT prototypes, and there are many potential applications for the technology that he is working on.

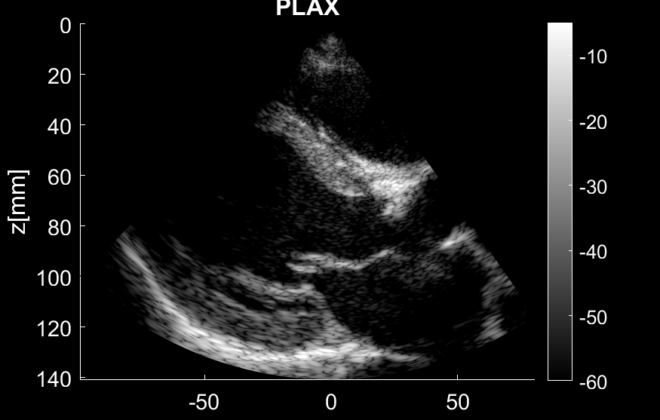

“In the medical market, PMUT has the potential where the miniaturisation, cost, being wearable and portable are decisive factors,” says Mansoori.

Examples are handheld ultrasound devices for point-of-care diagnostics, ultrasound patches for health monitoring and catheter-based probes for echocardiography.

“In the consumer and automotive markets, PMUTs have already been commercialised as fingerprint sensors providing higher security and time-of-flight sensors to measure distance in robots, drones, and autonomous vehicles. They can also be used as human-machine interface sensors, creating the sense of touch over distance in the metaverse,” Mansoori adds. “So, in my opinion, PMUT will be the next ‘little thing’ in the ultrasound world.”

Rewarding internships abroad

During his graduate studies, Mansoori has interned with two big companies abroad: “In 2018, I did an internship with one of our industrial collaborators, GE Parallel Design, in France. Later in my PhD, I did a six-month research visit in Milan, Italy with TDK InvenSense.”

As an intern with TDK, a leading manufacturer of PMUTs, he worked on the design of next-generation fingerprint sensors. “I designed some PMUT arrays as research prototype fingerprint sensors and have learned a great deal not only about the technology but also about teamwork and problem solving,” Mansoori says.

He is very grateful for these opportunities. “Through internships, you can kind of gradually start to transition from being a student to being an engineer working on real-life problems,” Mansoori explains.

Also, he appreciates that having had these internships in different countries has made him more flexible.

Learning how to “kose”

He describes his PhD as a valuable journey with ups and downs.

“It has had multidimensional learning aspects. One, of course, is technical, you become an expert in your field, but one is also about how you manage your time, how you deal with your colleagues, and how you network with other researchers,” says Mansoori.

In his spare time, he has mastered the Norwegian art of “kos”: “Since I came to Norway, I have started to learn new hobbies and tried to adapt to Norwegian culture, I think now I can “kose” like a Norwegian.” When asked for an example, he promptly answers: “One way is to go to nature and relax”.

This article first appeared in the 2021 CIUS Annual Report.

Wenche Margrethe Kulmo

-

Wenche Margrethe Kulmo#molongui-disabled-link

-

Wenche Margrethe Kulmo#molongui-disabled-link

-

Wenche Margrethe Kulmo#molongui-disabled-link

-

Wenche Margrethe Kulmo#molongui-disabled-link