The biased inventor – when an innovation fails

As a researcher in CIUS my job is to develop new knowledge, concepts, and methods to further science and innovation. In doing so, it is easy to be misled, or biased if you will, by one’s own ideas. This is a true story.

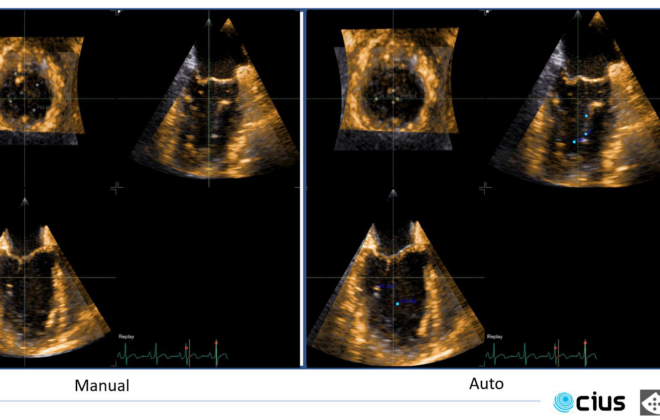

The Idea Fellow CIUS colleagues and I, recently came up with a new way of processing ultrasound data which we thought was very smart. It clearly provided better results when compared to state-of-the art methods. We worked hard for almost a year, tested the method in a range of scenarios with large amounts of data. It all matched up; the method was indeed better by all accounts. We could even quantify it, the holy grail of engineering.

In true CIUS spirit, we had regular update meetings with our industrial partner in the project. We discussed the method with their R&D team, showed results, implemented suggestions on improvements from them. The method was also tested, in a simplified way to reduce time, with realistic data from our partner. In the end we all agreed this was indeed promising. A decision was made to create a full pilot of the technology in the partners system for a potential commercial evaluation of the technology.

The pilot

Our industry partner then devoted internal engineering time for this task, which took several weeks of implementation and testing by experienced engineers and testing personnel. Precious time with a large range of concepts in the pipeline for testing in their product roadmap portfolio. We were all very excited.

When debugging came to an end and the method finally was running, the results were suddenly not at all that promising anymore. We were struggling to see real improvements in the data when testing the method in a realistic use case. This caused several weeks of frantic investigations into why this was the case, with re-runs of the research data, re-evaluation of the software implementation, and new testing. Still, same results: Hard to observe a significant improvement.

The air went out of the balloon. We were all quite disappointed, as we had all hoped this would represent a clear improvement, and we had invested so much time and effort into the project.

The art of failing

What happened here? Perhaps not an uncommon experience for many inventors. An idea seems very promising, but does it pass the litmus test? Checking all data in hindsight, the method did improve the data, and it was quantifiable, it was just that the quantitative level was not high enough to make a significant impact in a realistic setting. It also turned out we had taken some shortcuts in our development and testing phases, and not compared it to the optimal implementations of a similar concept our partner already had in their product. That was a mistake.

Also, the improvement came at a high computing requirement cost for our partner, almost overloading the system. As they stated: “There is an improvement, but it’s small. With no extra computational cost, this would have been a no brainer, but as of today, this is a no go.”

This was a lesson learned for all of us. As a researcher, I was perhaps too optimistic. I truly wanted a method I had been part of developing so much to work that I probably oversold it.

I was the biased inventor.

As a team our checks and balances were perhaps not rigorous enough, we were intoxicated by our own results. We have now learned that by doing more rigorous evaluations at an earlier stage in the project; checking the computational cost in more detail, making sure the implementation we tested was as close as possible to the existing solution, that is not taking short-cuts, we could have foreseen this. With this knowledge, we only become better at our job.

This is the art of failing.

The grit

We have not given up on the method. This was a first failure, never give up! That is also a very important lesson to learn. We are exploring the potential use of the method for other applications, and they do indeed look promising…

Svein-Erik Måsøy

-

Svein-Erik Måsøy#molongui-disabled-link

-

Svein-Erik Måsøy#molongui-disabled-link

-

Svein-Erik Måsøy#molongui-disabled-link