When innovation benefits research but not researchers

Technological progress without caring?

Recently archaeologists have debunked the myth that the great Egyptian pyramids were built by slave labour. It is great that we can now look at these majestic monuments knowing that the workers enjoyed good standards of employment.

This desire of enjoying goods that were produced without exploiting the workers has led to the development of the idea of “fair trade” and of its certification. Surprisingly, the most prominent technological revolution of our times, the digital revolution, has lagged behind. We can easily buy fair trade coffee or bananas, but a fair trade smart phone is very hard to find.

If we look at the contents that the internet has brought to us, things look even worse. Services that were once provided by highly qualified and well-paid professionals are increasingly freely provided by unpaid amateurs. As a result, the big companies that own the main digital platforms reap huge benefits from the generosity of the people who share, while many have lost their good jobs. The domain of research has its problems too. Digitalisation is often pursued overlooking the wellbeing of researchers.

For the greatest benefit of science

Scientific research and scholarship have been revolutionised by digital technologies and new opportunities for discovery have emerged. Researchers have new and powerful tools that give access to wealth of data and can save a lot of time and tedious work. Yet, some of these tools need a remarkable amount of work and time to be built.

A case in point are digital knowledge repositories. To build them, researchers are asked to upload and share the results of their research. Yet, a lot of work is needed to make these results most useful, accessible to other researchers and trustworthy. Data need to be structured according to detailed protocols that make them machine readable and their quality verifiable by prospective users.

The potential users of scientific digital repositories are broader than the readers of scientific papers and need to be reassured that the quality matches that of peer reviewed publications. The more interdisciplinary and diverse is the set of potential users, the more challenging is the task. But meeting this challenge is crucial, otherwise the expected benefit of the repository will be missed. A knowledge repository must be, and perceived to be, scientifically rigorous. At the same time, it should be accessible beyond the narrow disciplinary community. So, the findings cannot be presented in the same way as in a scientific paper. Further work is needed. And who shall do this further work? Researchers, of course.

Why are you not sharing? What’s wrong with you?

It is therefore not so surprising that these projects struggle to get enough data and knowledge from researchers. I call this the problem of the reluctant contributor.

The problem is well known and often framed as a conflict between the ethos of sharing and the individualistic attitude of researchers. Scientific culture, so the story goes, has long been based on being open and disinterested, while contemporary researchers are driven by ambition. They are interested in establishing their excellence and their reputation through publications.

These framing and narrative are both inaccurate and judgemental in a moralistic way. They are moralistic because they give the impression that researchers are ambitious and selfish to the point of betraying the disinterested ethos of science. They are inaccurate because many researchers are not really the masters of their time and of their data: they are constrained by the demands of their employers and by the need of securing their next contract.

The root of the problem is not individual values, but institutional culture. A managerial and competitive culture now governs research institutions, therefore researchers cannot afford to ignore productivity indicators. This leads to the well-known imperative “publish or perish”. Furthermore, a growing number of people now compete for resources that are limited and no longer expanding. Being good is not enough, researchers need to be better than their peers. To excel is to stand out. There is a tension between sharing and keeping a competitive edge.

So, contributing data to these repositories can greatly benefit research, but requires time and effort from researchers. It comes with costs, and risks. In a recently published paper (Fair trade in building digital knowledge repositories: the knowledge economy as if researchers mattered) I argue that researchers are not rewarded adequately for their effort and are struggling to meet ever increasing demands and duties.

Once upon a time there was a happy profession…

Until a few decades ago, researchers and academics reported high levels of professional satisfaction and mental wellbeing. But things have deteriorated quite sharply in the last thirty years. The world of research is increasingly populated by researchers desperately struggling to keep their position and securing the next temporary job. Competition and selection are fierce.

Too many well qualified researchers compete for few jobs, and employment conditions get worse: less job security, lower pay, heavier workload and higher expectations. Performance indicators keep growing. Researchers who fail to meet these high standards of productivity are seriously at risk of being left behind and having their research career coming to an end.

Researchers nowadays need to be extremely efficient and strategic in managing their careers if they want to stay in business. They need to set their priorities right. Moreover, this situation has led to a worrying rise of mental health problems among researchers, as shown by a growing body of research. So, how can people be expected to put extra time and work in activities not properly rewarded and acknowledged? Are the greatest benefit of science and society appropriate incentives for an overworked and precarious workforce?

Time for fair trade in knowledge production?

This picture of the situation suggested to me that it was time to apply the principles of fair trade to researchers and to recommend that developers of digital knowledge repositories should put the wellbeing of the researchers at the centre of their concerns.

These repositories, we are told, will bring about so much added value to society, industry and consumers. Great, but what about the researchers who produce and feed the content into the repositories? Should they not partake in these benefits? Should they not be offered some rewards that contribute to improve their working conditions, lighten their workload and lower their level of stress? This seems the ethical way of producing benefits for science and society. It would also be an effective strategy for securing the success of the repositories. Of course, it will have a cost. Is society prepared to pay this cost?

Responsible research and caring for the researchers

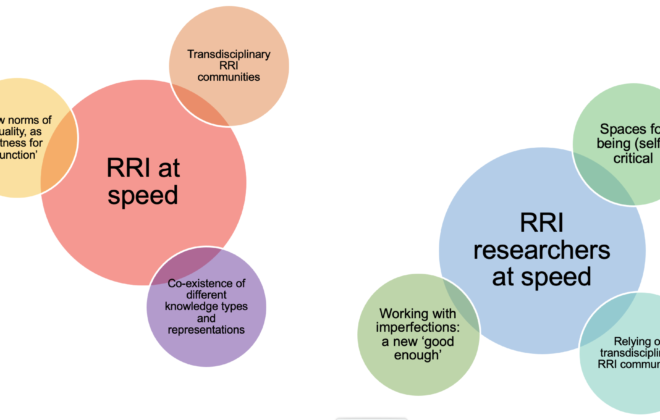

The idea of responsible research and innovation (RRI) has very much focused on the impacts of research and innovation on society and users. Yet, it seems not to have put enough emphasis on impacts on those who produce research and innovation. RRI is failing to notice that researchers are increasingly becoming a very vulnerable professional group, whose quality of life is declining.

Researchers surely have important responsibilities, but we should not forget that, just like any other worker, they have some basic needs for security, rest and recreation. If these needs are not met, it is less likely that they will be able to fulfil their broader social responsibility. If society shows care and concern for your wellbeing you are more likely to care for the wellbeing of society. This seems to be a basic assumption underlying the Nordic welfare state tradition and culture.

I suggest that this should also be a principle for RRI.

The licenses to the photos in the featured images is given by Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic. The collage is set up by the blog post writer, Giovanni De Grandis.

Giovanni De Grandis

Giovanni De Grandis has a PhD in Philosophy. In the last ten years he has worked in several transdisciplinary projects and initiatives in the areas of health, new technologies, innovation and public policy. He is the coordinator of the AFINO project and leads Work Package 2.