By Marius Warholm Haugen

The establishment of the French Royal Lottery in 1776 is a watershed moment in the history of France. The introduction of the Genoese numbered lottery system assured the success of a permanent lottery institution that would last for over sixty years, generating large incomes for the state. At the same time, the numbered lottery, with its combination of exorbitant prizes and terribly poor odds for the players, gave new vitality to the public debate concerning political and moral legitimacy of the lottery as a royal institution.[1]

The public debate not only took place in parliamentary speeches, pamphlets, philosophical and economic treatises, but also within the cultural domain, on stage, in novels, poems and songs, in memorialist writing, and in visual art. Compared to the political arena, these latter forms of expression address the lottery problem in a different language, placing them within a particular aesthetic framework; they may also be said to give privileged access to the issue in the contemporary social imagination. In the following, I will examine a few examples from the representation of the lottery problem in French literature and art in this period.

Before looking these examples, however, let us pinpoint the lottery problem as it appeared in the public debate. For the opponents of the lottery institution, the problem was, in fact, a set of problems. As a royal institution, the lottery entailed the exploitation by the Sovereign of his subjects’ passion for gambling, in a game where the odds were largely, to say the least, in favour of “the house”. Lottery playing was also perceived to cause extensive social and economic problems: poverty, addiction, ruin, and even suicide. Moreover, it shifted both energy and money away from productive work towards “sterile” gambling, it led to fraud and superstition, and could also be seen to contain a promise of social mobility as a threat to established social hierarchies.

For the lottery’s supporters, on the other hand, a major argument rested on international competition, on the (probably correct) assumption that foreign lotteries would draw money out of the country if no state lottery existed in France. In addition, they perceived the game as a form of “voluntary taxation”, putting emphasis on the institution as charitable and financially useful, while also arguing that the lottery could be a way of harnessing and tempering a propensity for gambling that would continue to exist also without the institution.

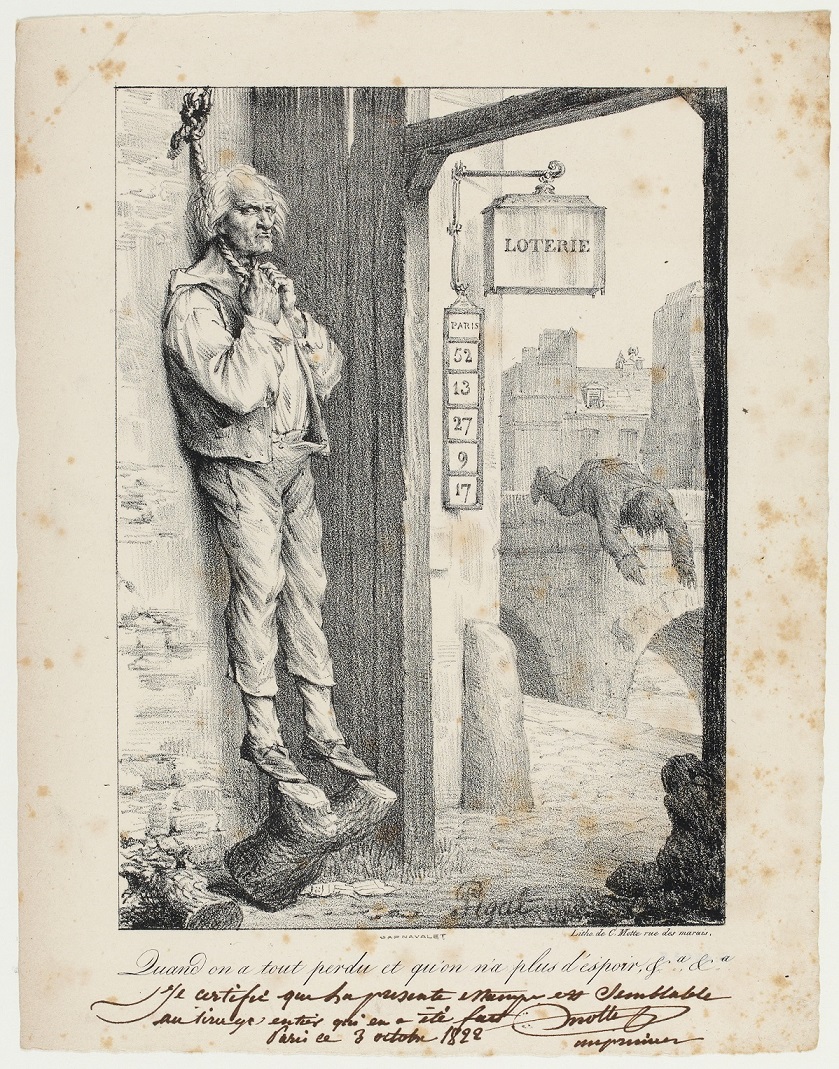

Coming now to the cultural representations of the problem, we can see that visual art presents us with particularly eloquent takes on the problem of social and economic misery associated with the lottery. In the 1824 print, “I have lost!”[2], we witness a poor mother, surrounded by her hungry kids, staring wistfully at the winning numbers displayed outside the office, with the losing ticket in her hand [figure 1]. The lottery, seducing the poor with its promise of a better life, leads not only to individual misery, but affects entire families and, as such, the very social fabric. The perspective is even darker in the 1822 engraving entitled “When you have lost everything and have no more hope”.[3] This image plays on a recurring topic of the public debate, namely the connection between the lottery and a perceived increase in suicides [figure 2].

In both cases, the lottery institution is represented metonymically by the vertical panel displaying the five winning numbers, establishing a striking visual contrast between the promise of fortune and the despair of the players. A third example illustrates the recurrence of this iconography, but also its possibility for greater ambiguity. The frontispiece of the French translation (1801) of Pietro Chiari’s novel La Giuocatrice di lotto [The (Female) Lottery Player] depicts two players, a man and a woman [figure 3].[4]

The man on the right signals, as in the two previous examples, the despair of the losing player, whereas the woman on the left, whom the reader would readily identify with the novel’s heroine, positively signals the suspense inherent to the game [figure 3]. The legend, “Have I won, have I lost? Read”, establishes an analogy between the suspense of the drawing and that of the novelistic plot, indicating how the lottery can be likened to narrative fiction in providing pleasurable uncertainty. Effectively, at the end of the novel, the heroine wins a fortune, the happy denouement coinciding with the drawing of the lottery. As such, the lottery institution becomes incorporated into a narrative representation of the game which is, at best, highly ambivalent.

In any case, the three images together show how the vertical panel of the lottery office came to signal the production of bedazzlement, hope, and suspense, but also of disillusion and despair. Thus, it visually references another recurring element of the lottery debate: the seductive power of the institution’s publicity apparatus. This apparatus is more extensively depicted in prose fiction, for example in Charles-Auguste Sewrin’s picaresque novel La Famille des Menteurs (1802). The narrator describes the lottery office as a place of seduction and alluring advertising, where rich and poor alike are lured to waste their money on “extravagant dreams”:

Wheel of fortune, booklets, sympathetic calculations, grand Albert, small Albert; their boards were decorated with ribbons, and piles of gold emerging from a cornucopia (in painting), forced the eye to contemplation, the heart to desire, the hand to touch. It was there I saw men covered in rags, bringing with them the fruit of their labour, and falling from starvation next to the cornucopia; the rich covered in diamonds, venturing very hard cash, for watercolour coins, and thousand other madmen of the same mould, basing their fortune on the extravagant dreams of their hollow brains.[5]

The narrator vividly depicts how the onlooker’s eye is “forced” to contemplate the iconography of wealth and fortune, through a publicity apparatus that instils the heart with desire, but which is also linked to various forms of superstition. He connects this to the seductive power of the lottery fantasy, operating its creation of suspense in the interval between the wager and the drawing: “A thousand shining fancies intoxicated my imagination until the moment of the drawing” (p. 241).

However, as in Chiari’s novel, the integration of the lottery into the plot weakens the critical potential. The narrator’s critique of the lottery is undermined by the novel’s ending, where the protagonist wins the big prize in the lottery, which appears as a Deus ex machina resolving all his problems. This contrast testifies to the more complex representation of the lottery and the lottery problem when produced in literary form. Although a critical, or even moralist, message is identifiable in many, if not all, cultural and literary representations of the lottery, the insertion of the motif within a larger aesthetic or narrative framework often brings with it a degree of ambiguity concerning the question of the political and moral validity of the institution.

[1] This text is partly based on a paper presented at the third Nordic eighteenth-century conference, “Rights and Wrongs in the 18th Century”, in Copenhagen 24–26 August 2022.

[2] Antoine Joseph Chollet (engraver) and Adolphe Roëhn (painter), “J’ai perdu” (Paris, 1824). Musée de la Loterie, Brussels: https://www.museedelaloterie.be/collection/jai-perdu

[3] Edme-Jean Pigal and Charles Motte, “Quand on a tout perdu et qu’on n’a plus d’espoir” (Paris, 1822). Musée Carnavalet, Paris: https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/en/node/141368

[4] Frontispiece in Pietro Chiari, Le Terne à la Loterie, trans. Jean Antoine Lebrun-Tossa (Paris: Debray, 1801), n.p. Digitized by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Y2-71158, http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb30237796t.

[5] Charles-Augustin Sewrin, La Famille des Menteurs (Paris: Chez Madame Masson, éditeur et libraire, 1802), pp. 239–40.

Marius Warholm Haugen

Marius Warholm Haugen is Professor of French Literature at NTNU. Specializing in eighteenth-century studies, he is particularly interested in transnational exchanges, circulation, and translation in and between Italian, French, and British literature. He will conduct research on the representation of the lottery fantasy in French print culture and its connections to Italy and Britain.