By Marly Terwisscha van Scheltinga

‘What would you do if you won the lottery?’ Although I do not remember the distinct occasions on which this question was posed to me, I do remember it coming up now and again from childhood onwards. Every time, the question was entirely hypothetical: as a child, I had no money to spend in lotteries (if this had even been legal), and as an adult, I have never once participated in a lottery. Still, the question is an evocative one, and fun to discuss. What would you do if you suddenly came into a monstrously large sum of money? Generous child-me liberally bestowed most of this non-existent money on charity, young adult-me would, rather vaguely, ‘invest’. But, as she earnestly told her friends, ‘she would probably keep working’. My friends generally agreed with this last statement, perhaps betraying a lingering Calvinist attitude in our Dutch minds.

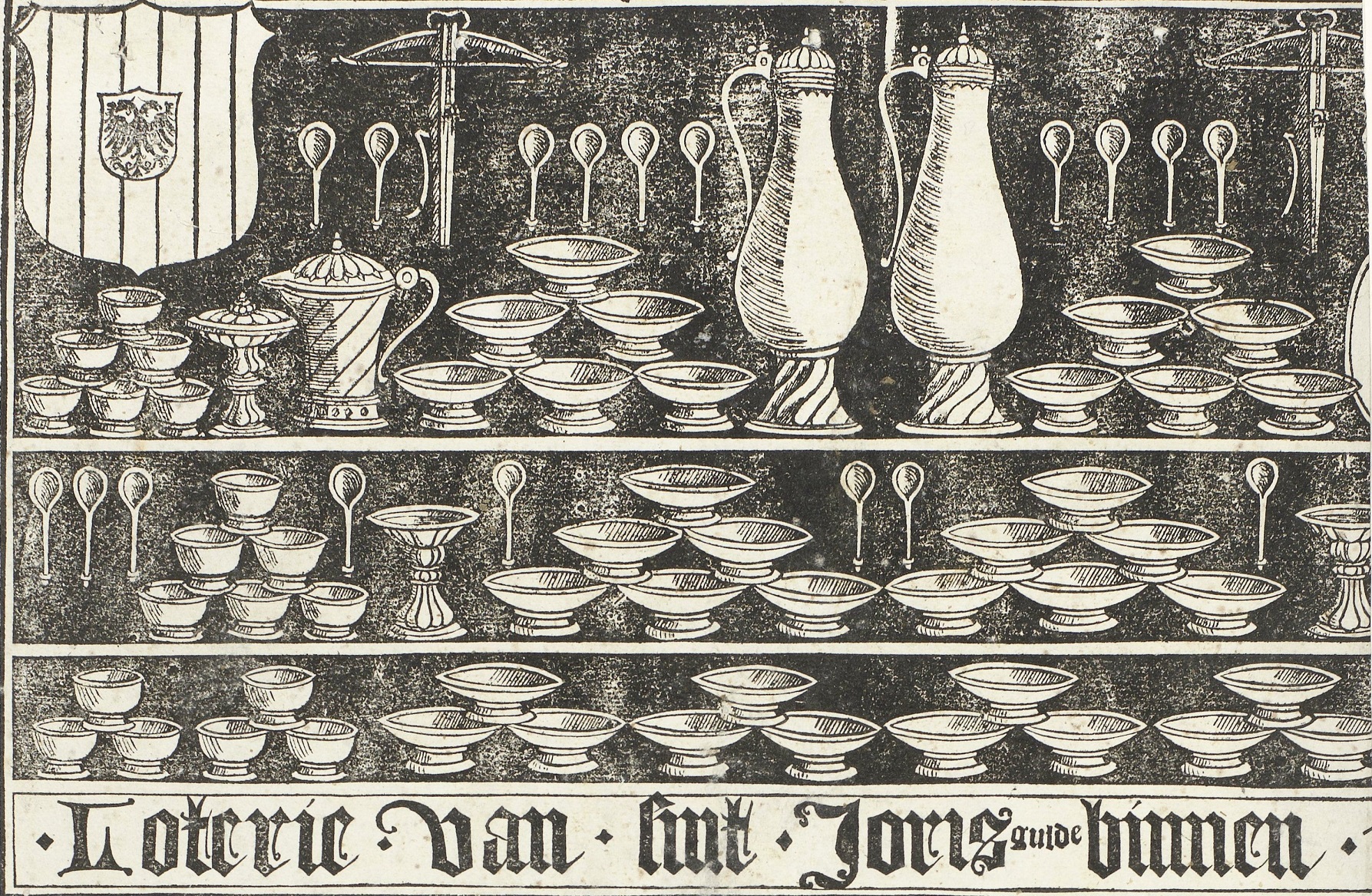

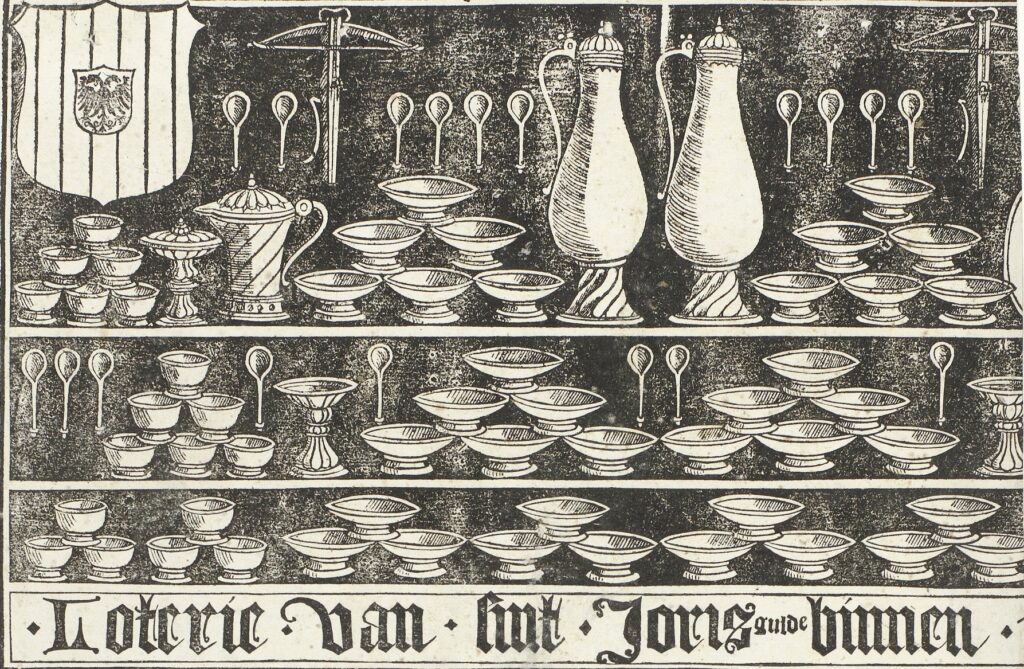

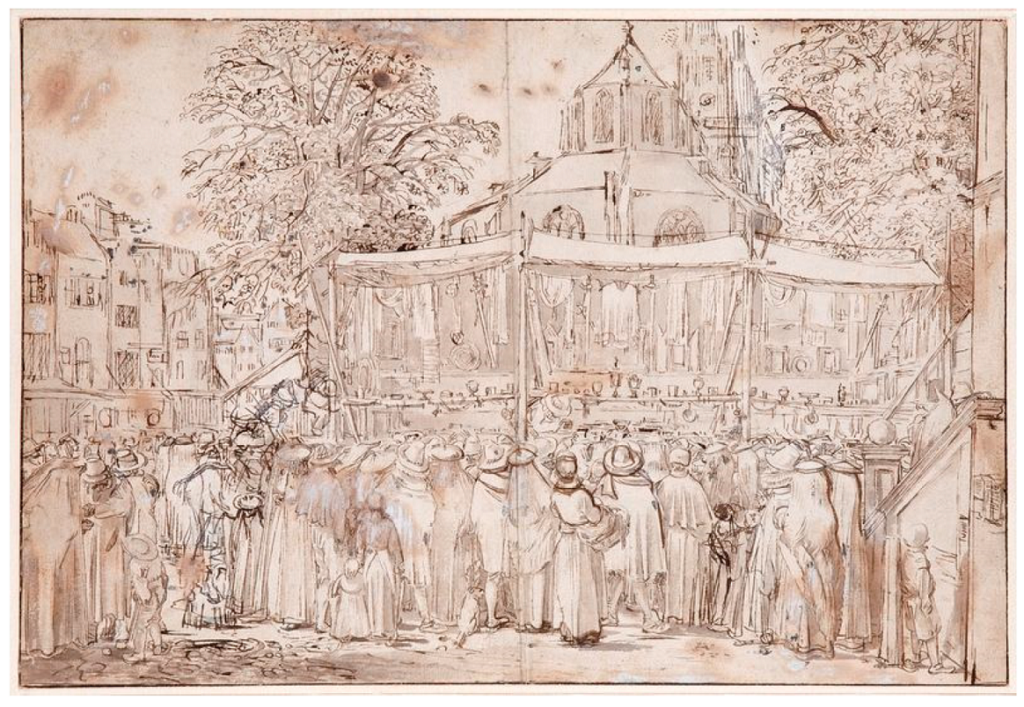

But what would people’s answers to this question have been in the past? More specifically, what would people from the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries have imagined themselves doing if they won the lottery? This might seem like an impossible question to answer, but there is, in fact, a source which tells us exactly that. Moreover, this source comes from people who were actually playing the lottery, making their answers slightly less hypothetical than mine have been. Lottery rhymes were short texts submitted by participants of early modern lotteries in the Low Countries when they bought their tickets. These texts were then read out when their ticket or tickets were drawn, as explained by Jeroen Puttevils in the previous blogpost. Lottery rhymes were quite flexible in form and subject matter, but most participants used them to comment on their own participation in the lottery. Of these participants, many revealed their fantasies and told the audience, and us, what they would do if they won the lottery.

God gaf, god nam

Hadde ick thoocxste lot, ick ate alle daghe eenen ghesuijckerde boteram

God gave, god took

If I had the highest prize, I would eat a sugared slice of bread every day

Sara Cotten from Antwerp, Bruges lottery, 1555

Of the participants who mentioned their fantasies, many talk about buying or consuming something. This something is usually a piece of clothing, or a certain kind of food or drink. In the lottery held in Bruges in 1555, Merten Calabers would “buy wine” with his prize, Jan Bos “a pair of new shoes” and Neelken Cornelis Hobickx’ daughter “would dress herself with it”. Fifty years later, in a lottery held in the town of Haarlem in 1607, Ariaenekin Fermaut “would buy a new dress” and Wauter Hubertsen, stocking dyer, proclaims that “all I win, is for the innkeeper”. These fantasies might seem slightly small and trivial to us, but both clothes and food were important symbols of status in the early modern period. Buying a new dress, or eating sugar (and especially every day) was expensive, and sent a signal to others that you were able to do so.

Interestingly, when it came to buying, eating and drinking things, men’s and women’s fantasies differed. Although both men and women mentioned food, drink and clothes, more men than women mention wine, and more women than men talk about clothes. Moreover, there are more men who dream big: Gijsphat van Noordermaet, participating in the 1555 Bruges lottery, would buy a horse, Anthonis Helias Montferrant says he would add a floor to his house in his lottery rhyme for the same lottery, and Jan Roeloff’s son, participating in the 1607 Haarlem lottery, would buy a ship. The only woman who has a similarly big fantasy is one Grietgen Claes. Her lottery rhyme, submitted in the lottery held in the town of Haarlem in 1607, says: “She has an old house/It is crooked due to its old age/If she gets the highest prize, she will take it down”.

Hector Pincoen, voederer van Antwerpen

Hadde hij thoocxste lot, hij soude sijn ambacht mede beginnen

Hector Pincoen, furrier of Antwerp

If he had the highest prize, he would start his trade

Bruges lottery, 1555

Another difference between men and women relates to work. There are not that many work-related fantasies in the lottery rhymes, certainly not as many as the fantasies of consumption. Still, we find a few participants whose dream does involve work, or, in some cases, no work: in the Bruges 1555 lottery, Jans Sijmoens says the prize money would “make him a merchant again”, and Jan Laenssen from Amsterdam thinks about his son’s career, and says he would make him a priest. On the other hand, Lowijs the mirrormaker, participating in the same lottery, “would no longer make mirrors”, Barber Jans, in the Haarlem 1607 lottery, “would spin no more” and Katrijn Jacobs’ daughter, a participant in a lottery held in Delft in 1564, “would no longer serve”.

Although the numbers are small, it is telling that none of the women sees the prize as a way to advance in their work, or get into another type of work. Instead, most of them imagine a life where they do not have to do the work they are currently involved in anymore. Although there are some men who do the same, others dream instead of becoming a master in their trade, or setting themselves or their son up in a new career. This reflects the realities of work for early modern men and women. Although women worked, and were in fact active in a whole range of fields, most gained access to this work through marriage, rather than through apprenticeship, like men did. Whereas men might use the prize money to change their position (going into an apprenticeship, or going from apprentice to master), women could not as easily advance in their work by throwing money at it. Much of the work open to women, such as spinning and serving as a maid, was moreover low-valued and low-paid, and did not offer any opportunities to advance. The women in these lottery rhymes seem not to have found much pleasure in it either, so that continuing it when it was no longer necessary was not something they thought of doing. Of course, when young-adult me said they would still work, even if they won the lottery, the work they had in mind would not have been the kind of work these women were doing either.

Grietgen Pieters ben ick geheeten

Inde lange veerstraet ben ick geseeten

Creech ick den hoochsten prijs, ick zouder den armen niet vergeeten

Grietgen Pieters is my name

I reside in the Lange Veerstraat

If I got the highest prize, I would not forget the poor

Haarlem lottery, 1607

Not all fantasies were self-serving. Like child-me, many participants said they would give (part of) their prize to charity. Often the terms were quite vague: Annittgen Aelbrechts’ daughter from Delft “would not forget the poor” in the 1564 lottery held in her hometown, and Cornelis Plavier in Middelburg, who participated in the Bruges lottery of 1555, “would be thoughtful of the poor”. Others were more specific in describing the amount of money and/or the beneficient: in the same Bruges lottery, Lisbet Aengels from Rotterdam would give the poor “a hundred guilders”. Jan Philippo, who participated in the Haarlem lottery of 1607, “would give half to the old men’s home”.

Pledging to charity became very common in the lotteries of the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth centuries. These lotteries were organised to raise money for a charitable cause. This in itself was not a new phenomenon. What was new, however, was the heavy emphasis on charity in the way the lotteries were promoted. Buying a ticket became an act of charity in itself, and many participants stress that they bought a ticket ‘out of love’ or ‘not out of greed’. This atmosphere probably inspired participants to promise further charity if they won something. The Haarlem 1607 lottery was meant to raise funds to build an old men’s home, which prompted many participants to pledge their prize to this specific cause. There is one intriguing exception though. Cornelia Jan Verwers’ daughter’s lottery rhyme states that “the lottery is done for the old men/If she could obtain any prize, she would give it to the old women”. This act of gender solidarity was not followed by others.

Whether or not any of these people got to fulfil their fantasies is unfortunately a question we cannot answer. The chances that they won anything – and especially the main prize – were very low. Still, the fantasies themselves can tell us a lot about what was deemed desirable in early modern society, and if and how this differed based on gender. Moreover, the lottery rhymes can give us a glimpse into a moment of ordinary people’s lives in which they were able to dream.

Marly Terwisscha van Scheltinga

Marly Terwisscha van Scheltinga is a PhD student at the University of Antwerp. She has a background in literary and medieval studies. Her project ‘A Woman’s Lot’ focuses on the way women in the early modern Low Countries used lottery rhymes to speak out in public.