By James Raven

The New Year will mark the beginning of the thirtieth year since a state lottery was re-introduced in Britain. That lottery arrived with almost no notion that a state lottery had been inaugurated almost exactly three hundred years previously. In 1992 the Lottery Act was passed, with an expectation of the lottery being operational by 1995. Against residual doubts and opposition, comparisons with state lotteries in Europe and America were used to justify and promote the advantages of the Act. Government ministers and press reports also emphasized the absence of lotteries in Britain. During the twentieth century, it was noted, gambling was reluctantly sanctioned, with Football Pools taxed under the Pool Betting Duty of 1947. The Betting and Gaming Act of 1960 legalized private casinos, and a year later, bookmakers were also legalised, to become, during the next few decades, one of the most popular staples of Britain’s High Streets (and suburbs). State premium bonds, introduced back in 1956, continued to attract punters and became an established part of popular personal financing options, but the original stake (if devalued) was never lost.

A state-sanctioned lottery remained a taboo. The Thatcher government piloted a National Health Service Lottery in 1988 but the scheme was cancelled for legal reasons before its first draw. Margaret Thatcher herself was unequivocally opposed to a state lottery, despite the findings of a commission that suggested such gambling for the benefit of the state might be trialled. Hardly any mention was made that state lotteries flourished in Britain and Ireland for one hundred and thirty years from the reign of William III to that of George IV. More than that, from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century Britain went to war on the proceeds of state loans raised by lotteries. And now a commission allowed a Bill to come forward for the lottery’s re-establishment. But Mrs Thatcher would have none of it – a lottery ‘fantasy’ was exactly that, a morally dangerous route of delusory make-believe, even if proceeds were put to good causes.

On 20 November 1990 Mrs Thatcher resigned: for those supporting the idea of a Lottery, including the new Prime Minster, John Major and his new Culture Minister, David Mellor, the way was clear for the lottery’s re-introduction (or, as it seemed to most, its inauguration). Plans were announced and an Act passed. I began to prepare to write about it.

On 19 November 1994, the first of the new National Lotteries in Britain was drawn, and the following account is drawn from my diary entry at the time (I was writing newspaper articles about the history of the lottery to inform the public that there was nothing new about the principle of a state lottery).

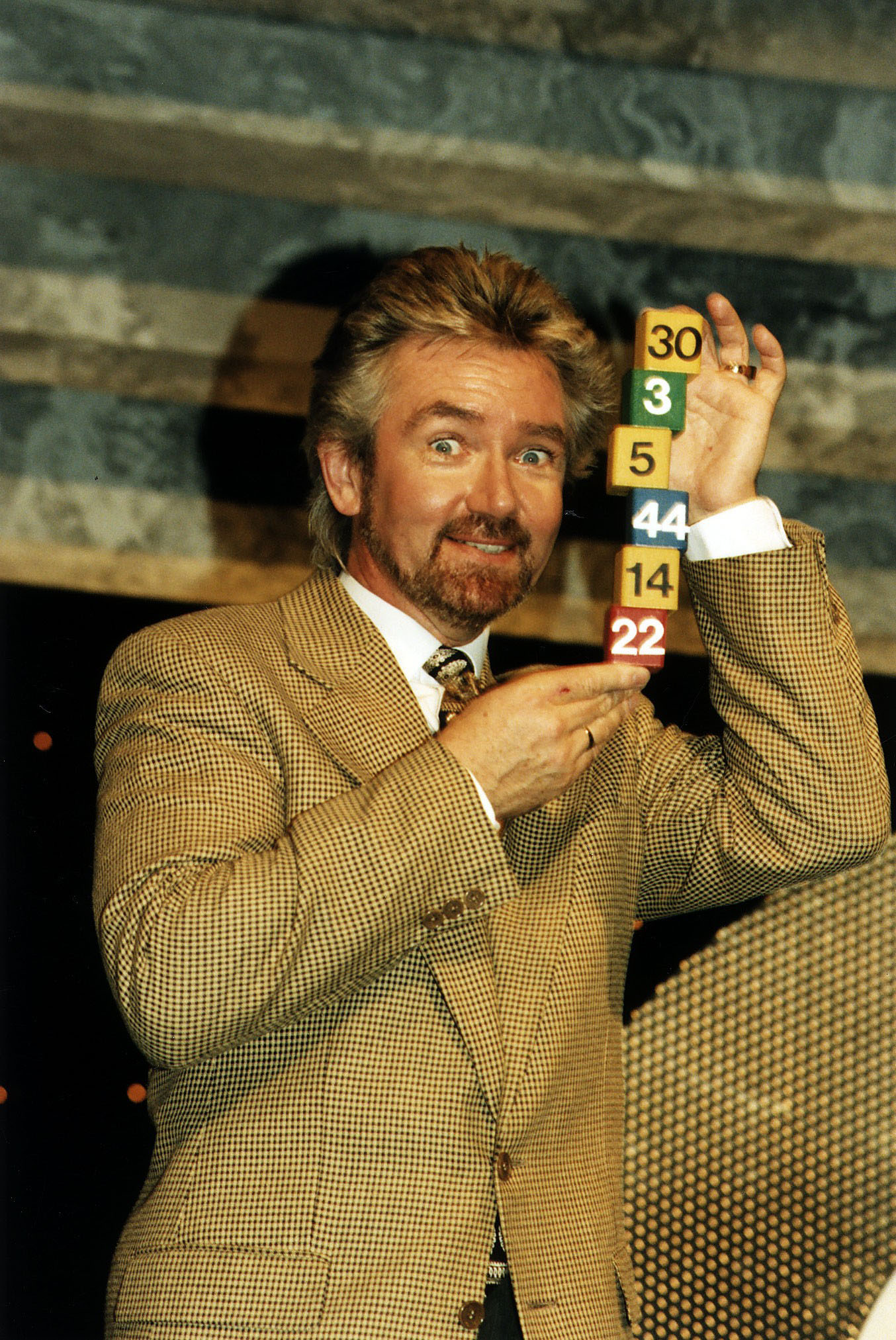

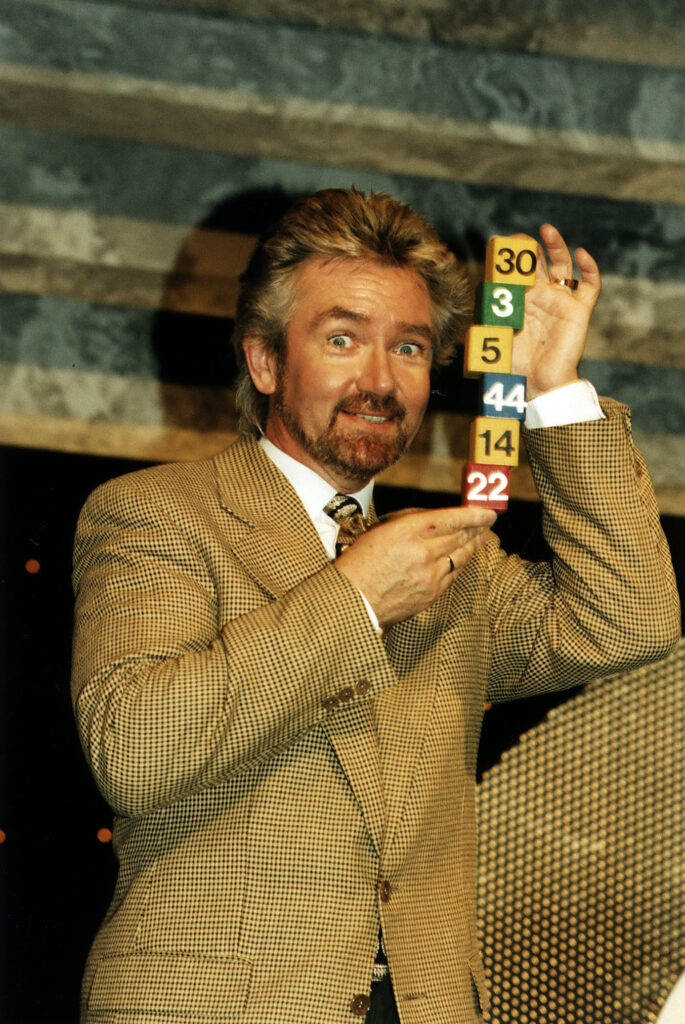

The launch of the lottery on 19 November comprised an hour-long television ‘special’ from the city of Nottingham (click here for a clip from the drawing). London, it seems, was deemed too obvious: the new lottery was to be embedded in the central Midlands of Britain. In the warm-up words from Broadcasting House, “the big moment has arrived – live and exclusive – on BBC1”. The state broadcaster assumed the monopoly of lottery coverage. The next sixty minutes featured a patronising game-show in which 49 ‘ordinary souls’ from different parts of the country competed for the right to start the lottery draw machine.

During this first modern British state lottery spectacle, the contestants on screen were whittled down to a final two by a series of five games. Each game represented one of the five ‘good causes’ that were together able to claim 28% of the total lottery takings. The first game, illustrating the National Heritage Fund – “our heritage is under constant threat” – required one of the pre-selected teams to identify the most valuable antique from a selection of objects ranging from a backgammon set to Charlie Chaplin’s cane. Inspired by a madly clapping studio audience, Michelle guessed that a Shakespeare first folio was worth a million and won through to the next round. A few minutes later, sport was introduced as the second beneficiary of the Lottery. Boxer Frank Bruno and darts-player Eric Bristow acted as goalkeepers in a “who-scores-most-wins” round. A National Lotteries Charity board, the third good cause, was publicised by a game in which Aileen persuaded “Conan” an inmate of the Battersea Dogs Home to run towards her. Another short film narrated by Stephen Dorell, Heritage Secretary, introduced the Millennium Fund and a game followed in which (for a reason not entirely clear) groups of contestants had to be arranged to weight as near to 1000lb as possible.

(Image credit: © Matt Brown, accessed via Wikimedia Commons)

In an unabashed nod to past national heroism (if in fact to fantasy history) three machines, named Guinevere, Lancelot and Merlin were revealed as the means whereby the draw was to be effected. John Willan, the ‘Drawmaster’ put the balls each 51mm across into the machines. It was announced that 25 million tickets had been sold for the first draw and a Ms Gretton in Nottingham interviewed one Milton, the last person to buy a ticket in the city before the 7.30 p.m. closedown.

The programme itself looked two ways; we were supposed to take the occasion seriously despite the paraphernalia and while Noel Edmonds, specialist in Saturday night popular TV entertainment hosted the show in which he often placed his tongue in his cheek – “only the British could cheer half a ton of metal,” he said, as the Draw Machine entered with smoke and flashing lights.

(Image credit: © Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy Stock Photo)

The newspapers greeted the event along sheet-lines. The tabloids praised the evening draw as a triumph; the qualities were aghast at the crude populism of it. Moreover, the more serious newspapers asked questions that were in fact centuries old – how best to secure a monopoly for the state, how to police it, the manner of its management, how to judge its morality, and how to cope with the sensationalist coverage of its draw – and of the winners. Beneath the concern to protect the poor and simple from vices they do not understand was also a basic concern about non-productiveness. Risk and gambling are acceptable amongst those able to afford it, but not amongst the unfortunate. Does democracy therefore bring gambling closer? Does a less religious age encourage it?

At the time, I noticed how remarkably similar these questions were, not just to eighteenth-century commentaries and those in the early nineteenth century that contributed to the protest at the time of the lottery’s abolition, but also to the questions raised by the last major historian and chronicler of the British and Irish state lottery. L’Estrange Ewen, in writing his straightforward account of the lotteries asked “if every article or action which tempts a person to do what he ought is to be abolished, what should we have left?” are we “to prevent ships sailing because the passengers are liable to be drowned” (Lotteries and Sweepstakes (London, 1932), pp 355–7). He, like the red-tops in fact, was ultimately favourable to the lotteries – but largely because they might promote good works and because the law was inconsistent in allowing the poor to be robbed or deluded by other fantasies. What many of us predicted at the time, however, was that “the good causes” were soon to be replaced by a general revenue pot – that the lottery luring the poor to play was soon simply only to benefit the Treasury directly.

James Raven

Professor James Raven is a Life Fellow of Magdalene College, University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of the British Academy. He is a renowned book historian who has researched and published since 1991 on the British state lottery. Raven gave the Mellon Lectures at Yale University (Macmillan Centre) in 2010, on ‘Histories of the English State Lottery’ and his book for Oxford University Press entitled Lottery Lives is near to completion and submission.