Christmas! A time for giving, a time for helping people in need, a time for those who are blessed with plenty to share with those who have little, not least in these war-torn days with levels of poverty and hunger increasing worldwide. Well, it’s an appealing way of thinking, but it’s not a universally held view of the festive season – either now or in the past – and it doesn’t seem to be the view advanced by ‘The Lottery, a Christmas Tale’, a short story printed in a seasonal anthology from 1775.

For researchers exploring the history of lotteries, source material can pop up in unexpected places, and this is the case with this little lottery tale found within the pages of The Christmas Frolick; Or, Mirth for the Holidays. This short book, published in London, is a collection of stories, songs, jokes and anecdotes – all intended to provide entertainment during the festive season, and, as the subtitle puts it, ‘to warm the Imagination, raise the Spirits in the gloom of Winter, and procure, what every one wishes, A Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year’.

In what manner does ‘The Lottery, a Christmas Tale’ warm the imagination and raise the spirits? Running to just two pages, it tells the story of Lucinda, a young lady of Lincolnshire, who is courted by several suitors who believe that she will inherit her father’s fortune. Her father, though, dies insolvent, and the suitors turn tail – all but a Mr. Freeland, a worthy man of means (with a name suggesting a mercantile profession: it recalls ‘Sir Andrew Freeport’, the merchant of the earlier Spectator essays). Lucinda selflessly refuses Freeland, not wanting to burden him with a wife who brings no fortune. But then, in this tale of rapidly changing luck, she inherits £12,000 from an uncle, at which point she plans a trick – or a test of male virtue – and it is here that the lottery comes in: she lets it be known that she has won a £10,000 prize in the recent draw. The suitors renew their courtship, all except for Freeland, who doesn’t want to appear to be a fortune hunter. When the actual winner of the £10,000 prize is announced in the newspapers, the suitors are enraged and abandon her again. Lucinda reveals the true situation to Freeland and they are happily united. But there is more joy in store for the couple. ‘What heightens the Beauty of this Story’, the final sentence informs, ‘is, that Mr Freeland obtained a Prize of 5000 l. in that very Lottery, which, as his Fortune was ample, he settled on Lucinda the Day preceeding their Marriage’.

The device of the supposedly lost fortune as a generator of plot would have been familiar to many readers in 1775. They might, for example, have encountered it at the theatre in Charles Macklin’s popular farce Love à la Mode, which similarly has a heroine pretend to lose her wealth to test the intentions of her admirers.

Readers would also have encountered numerous stories with comparable ‘virtue rewarded’ plots, for they were a staple of literary culture. One of the most popular examples was Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela, from 1740, which was actually subtitled Virtue Rewarded.

Lucinda and Freeland display a conventional type of virtue. In this miniature romance, both show that they are not in the marriage game for the money; they are free of avarice. At the same time, though, they are shown to be preoccupied with money, with Freeland’s implied trade and Lucinda’s devaluation of herself as a marriageable commodity when her father dies penniless. And their reward, alongside gaining each other, comes in the form of money – an absolute deluge of it, none of it really needed since Freeland already has his ‘ample’ fortune.

The spirits and imaginations of readers may well have been raised and warmed by this ending – by the couple’s double luck, as inheritance and the lottery render them staggeringly wealthy, and by the neatness and irony of a pretended lottery win being followed by an actual lottery win. But others may have thought that the story ends too soon: we are given no hints as to the couple’s future; we are told nothing about what they might do with their money. In Richardson’s Pamela, the poor heroine gains her reward – again it comes in the form of marriage to a wealthy man (in this case, a sexual predator who she has managed to reform). But importantly, Richardson’s work doesn’t end quite there: it rather goes on to show Pamela performing acts of benevolence and charity – continuing to be virtuous by stretching a generous hand out beyond her home. ‘The Lottery, a Christmas Tale’ concludes without such a coda; it doesn’t quite fulfil expectations.

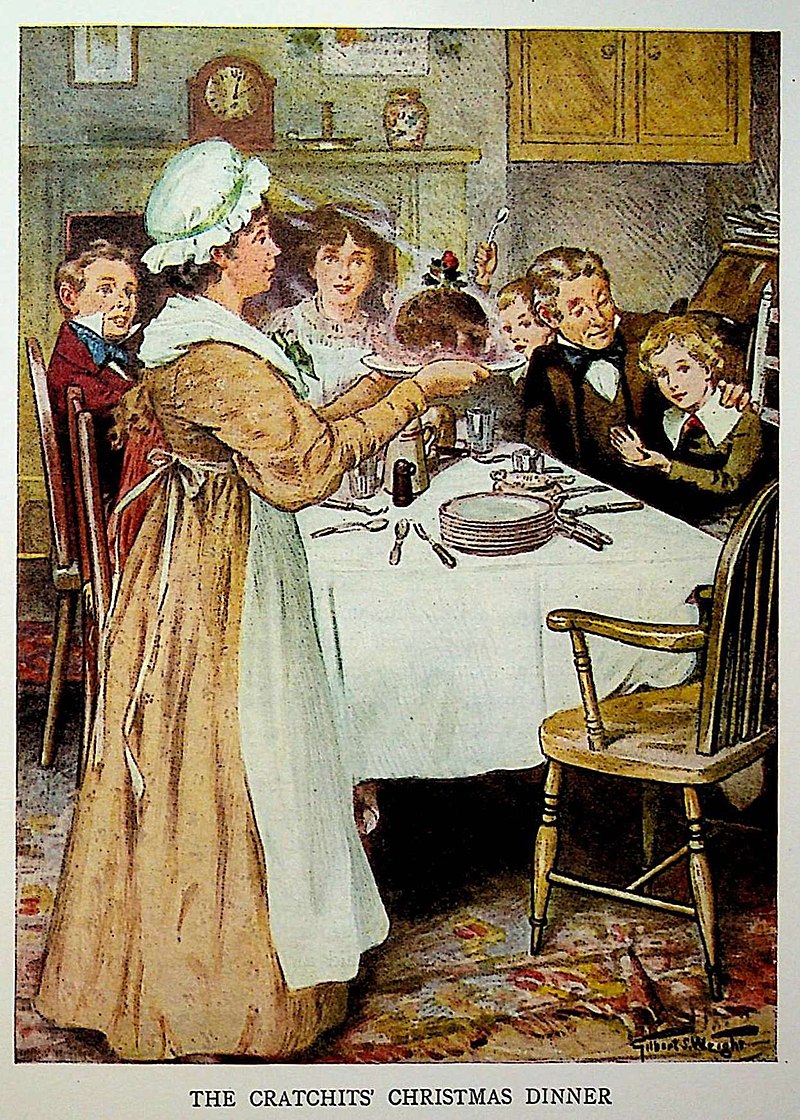

The story may also be said to defy conventions of Christmas tales, but here it should be observed that, in its own day, such conventions were hardly well established. Still, it may still be instructive to compare it with that apogee of festive tales, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843), for the stories both revolve around money but they show it flowing in completely opposite directions. Money is at the core of Dickens’s celebrated telling of the reform of Ebenezer Scrooge, from miser to festive philanthropist, and the basic trajectory that money follows is from individual/private to public/collective. With Scrooge’s moral transformation, the sums of money that he is so protective of at the start of the story come to be distributed to the needy of London. Money is dispersed rather than gathered; its potential is activated in the name of virtue; the poor Cratchit family are able to dine on goose. In ‘The Lottery, a Christmas Tale’, however, we see the opposite, since what a prize lottery does is gather money from a large number of people – those who have bought tickets – and puts it in the hands of the few. Lucinda and Freeland’s private gain comes at the expense of collective loss. Is that in the spirit of Christmas?

But perhaps depicting an already wealthy lottery winner in a type of feelgood story of this kind is innately problematic, since lotteries have long had a troubled connection to ideas of public good, whatever the efforts to promote them, both in the past and today, as schemes that benefit not just lucky individuals but society at large. It is a basic rule in the world of gambling that there can be no winners without losers.

Back in 1775, readers of ‘The Lottery, a Christmas Tale’ would have been made acutely aware of this if, as well as enjoying The Christmas Frolick, they had been keeping an eye on the newspapers. A draw for the state lottery was underway at London’s Guildhall at the time – the procedure could go on for more than six weeks – and if they picked up, for example, the Public Advertiser of 23 December they could read of some lucky winners who had bought tickets from John Molesworth, a renowned lottery agent:

No. 14,575, drawn on Thursday last a Prize of 5000l. is in Mr. Molesworth’s Calculation, and was sold the 26th of October at the Offices, No. 67, Holborn; No. 30, Fleet-street; and No. 34, King-street, Cheapside; where also have been sold in the present Lottery, No. 59,276 a Prize of 5000l. one 2000l. in Shares, four 1000l. and one 500l. all which Tickets will appear at the Exchequer, indorsed by Mr. Molesworth.

Opening the pages of Lloyd’s Evening Post for 22-25 December, though, they would have encountered a much sadder story:

The young Gentleman who was found hanging in his bed-chamber last week, at his lodgings in King-street, Soho, is said to have lost a large sum of money in lottery insurances, which caused him to commit this rash action.

We might spare a thought for the poor man – and perhaps more than a thought for others today in similar states of desperation, whether induced by gambling or other causes. It would be in the spirit of Christmas to do so.

Paul Goring

Paul Goring is Professor of British Literature and Culture at NTNU. He has specialist interests in theatre history, the actor and playwright Charles Macklin, the life and works of Laurence Sterne, and the mediation of news.