Lottery advertising often employs fictional narratives to motivate real-life outcomes from their audiences. This was true even in 18th and early 19th century England when lottery office owners appealed to the imagination of their patrons to motivate ticket sales. This strategy would involve visualization through text and images of a future fantasy in which the patron has won the lottery. Not only did the advertisements entice with the notion of fictional wealth, but they also lured players by equating winning the lottery with fulfilling dreams of love and marriage.

Contemporary readers will perhaps rebuff the idea that love has anything to do with money, but this coupling was certainly not out of reach for desperate advertisers in the early 1800s. Ghastlier than the conflation of winning money with winning love, is the messaging by these advertisements that money is in fact a greater prize than love. This messaging especially took hold of advertisements for lotteries on Valentine’s Day, a popular lottery draw date, as draws often coincided with holidays or special days of the year (Grant, G.L., The English State Lottery 1694-1826, 2009, p.6).

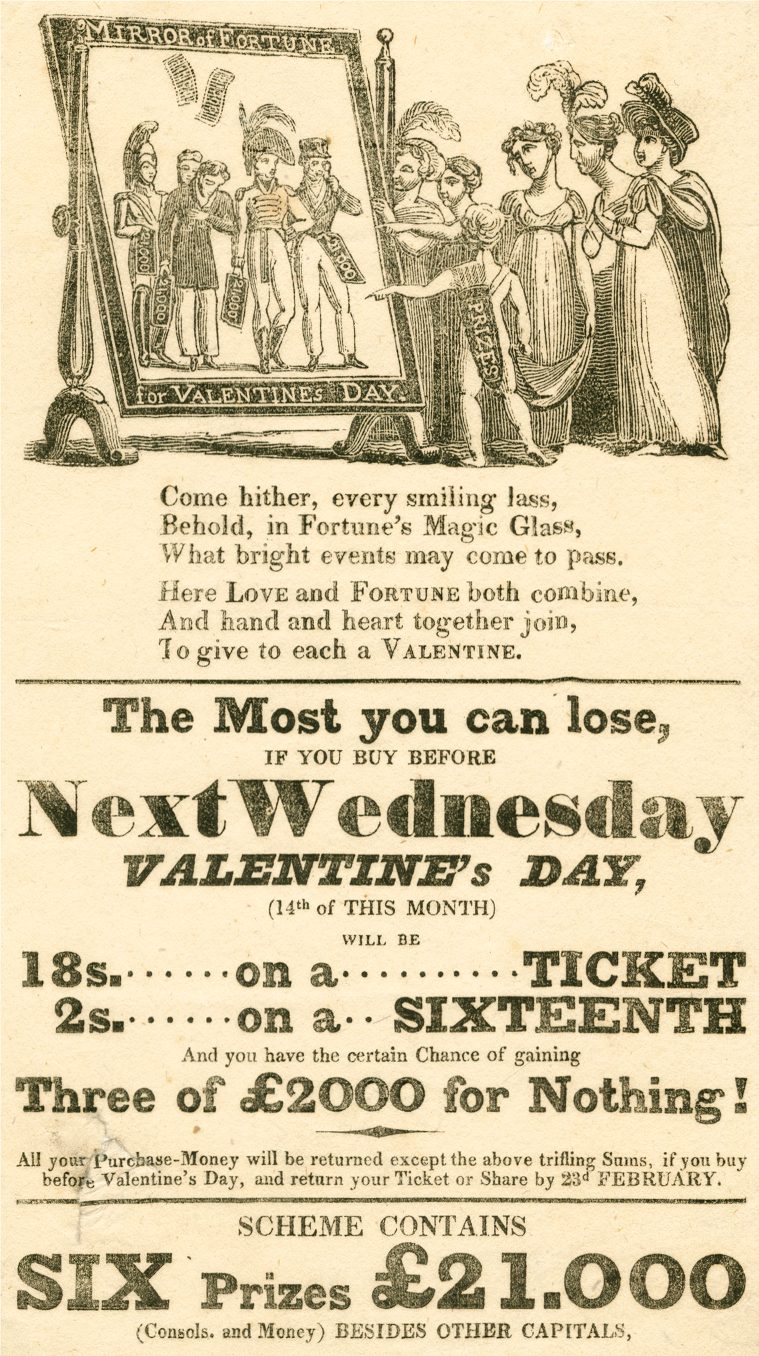

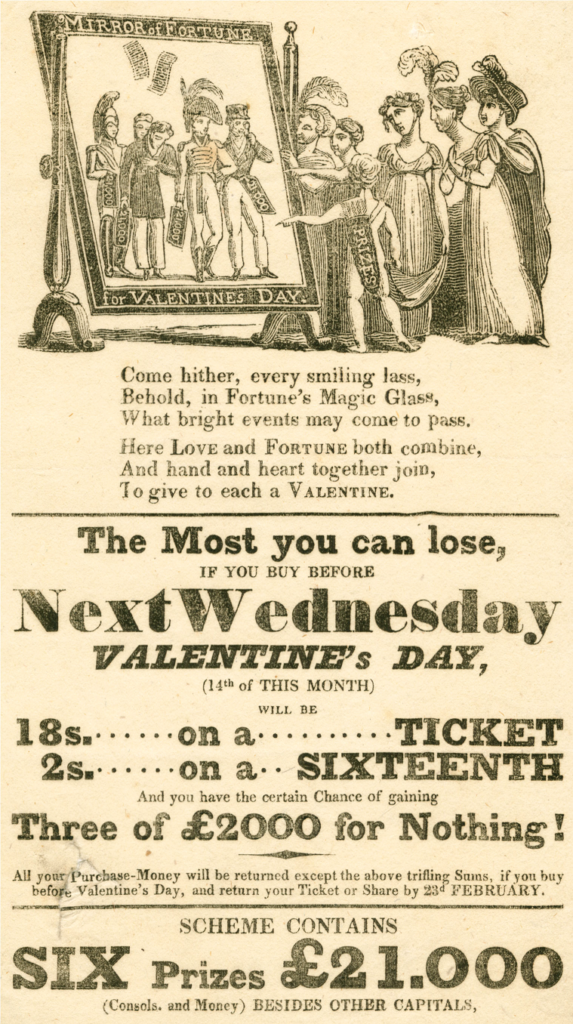

Above is an example of a general Valentine’s Day lottery advertisement that conflates love and lottery from the early 1800s. Longing women gaze into a ‘Mirror of Fortune’ shown to them by Cupid, whose quiver of arrows labeled ‘PRIZES’ awaits both his draw and the eventual draw of the lottery. The mirror-enclosed gentlemen of the future are all dressed in a variety of well-to-do clothing that suggests their occupation, all have won lottery capital prizes, and all are awaiting the “past” Cupid’s arrow and a flock of marriage-hungry ladies. As marriage is a necessity for their monetary gain, the ladies will claim these high-ranking, wealthy men as their prizes, aided by the precision of cupid’s aim.

The text similarly reinforces the combination of marriage and fortune, claiming that in the future: “Here Love and Fortune both combine, / And hand and heart together join, / To give each a Valentine.” Valentines, normally received by the literal hand and the figurative heart, in the context of this advertisement can be extended to lottery tickets: held in the hand and felt in the heart. The material paper of the ticket creates both an imaginative space for the fulfillment of monetary and marital dreams and a practical space where love and fortune can be pursued in parallel. The romantic errand standing between the ‘present’ advertisement viewer and a future fulfilled with riches and love is merely buying a *winning* lottery ticket.

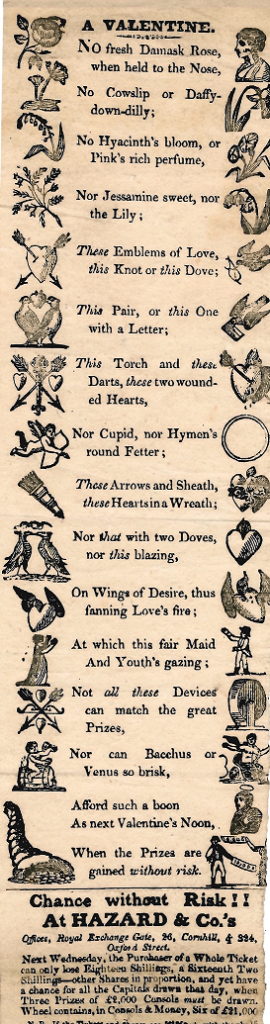

This second advertisement pictured above was commissioned by Hazard & Co. Lottery Office in the early 1800s for a Valentine’s Day lottery. It is entitled, “A Valentine,” suggesting that the reader is to now contextualize this lottery advertisement as a type of Valentine that can be felt in the hand and the heart. It builds a creative verse that combines image and text, both of which draw upon conventional “devices” for love. It begins with the bouquet to get the reader in the mood: the Damask Rose, the Cowslip, the Daffy-down-dilly, the Hyacinth, the Jessamine, and the Lily. Then the verse moves onto a Pair of doves and One with a Letter, before using imagery of classical mythological figures and emblematic hearts: in a wreath, fanning fire, with wings, wounded, and blazing (to keep the rhyme, the reader must fill-in the missing text with the visual heart for this line: “Nor that with two doves, / nor this blazing ____”).

The reader might notice that these lines, although functioning to build a wholistic and romantic illustration of love’s devices, begin with or are the continuation of the negation ‘No’ or ‘Nor.’ It is not until the end of the poem that the reader fully understands what these symbols of love cannot amount to: no matter how noble, love cannot compare to winning the great prize of the lottery. The line, “Not all these Devices can match the great Prizes,” leads to the selling point of the advertisement: riches won now are more valuable than centuries of emblematic love. The last line of the poem, “When prizes are gained without risk,” is surrounded visually by a cornucopia overflowing with coins and two winning lottery patrons waving their tickets at the reader. Risk here serves two purposes. First, it notifies the reader of a financial incentive common in lottery practices that at least a portion of the ticket price would be guaranteed to win if the patron followed the conditions in the fine print. Secondly, it implies that love, contrary to lottery playing, comes with risk. Whereas the contrast between love and lottery presents both as games left up to chance, playing the lottery is a safer bet, thus the poem concludes that wealth is better than love.

Modern viewers, who perhaps would prefer love to be unadulterated and absent of monetary influence, might be disappointed to find that these advertisements held money in greater or equal footing to love. The actionable goal of the fantastical world-building in these advertisements was intended to get shoes in the doors of lottery offices and money in the pockets of lottery officers. Despite relying on dreams of love and marriage to build a desire to play, the poems, narratives, and visualizations of advertisements often ended with gaining wealth from the lottery. It is no surprise then that we find selling the product to take precedence over promoting more noble pursuits, even in a period when advertising was still finding its shape as a media.

Natalie Devin Hoage

Natalie Devin Hoage is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Language and Literature currently researching the “lottery fantasy” in state lottery advertisements from the eighteenth-century to contemporary times. Her archival research spans across Europe and includes Scandinavia, The Netherlands, The U.K. and Spain.