How does one react when suddenly winning a huge prize, and one’s status changes overnight from poor to rich? This is a fantasy most of us have played with, and which the Norwegian national lottery institution, Norsk Tipping, have made into their trademark, through their previously mentioned ad campaigns. In addition, literary fiction provides a rich portfolio of winners, imagined and actual, who strikingly often let their prizes (or the thought of their prizes) get to their heads in a ridiculous, if not to say deterrent way. The lottery winner, whether an actual or imagined winner, has simply proved to be a recurring comic type, i.e. one we can both laugh at and learn from, right from the 18th century up until today.

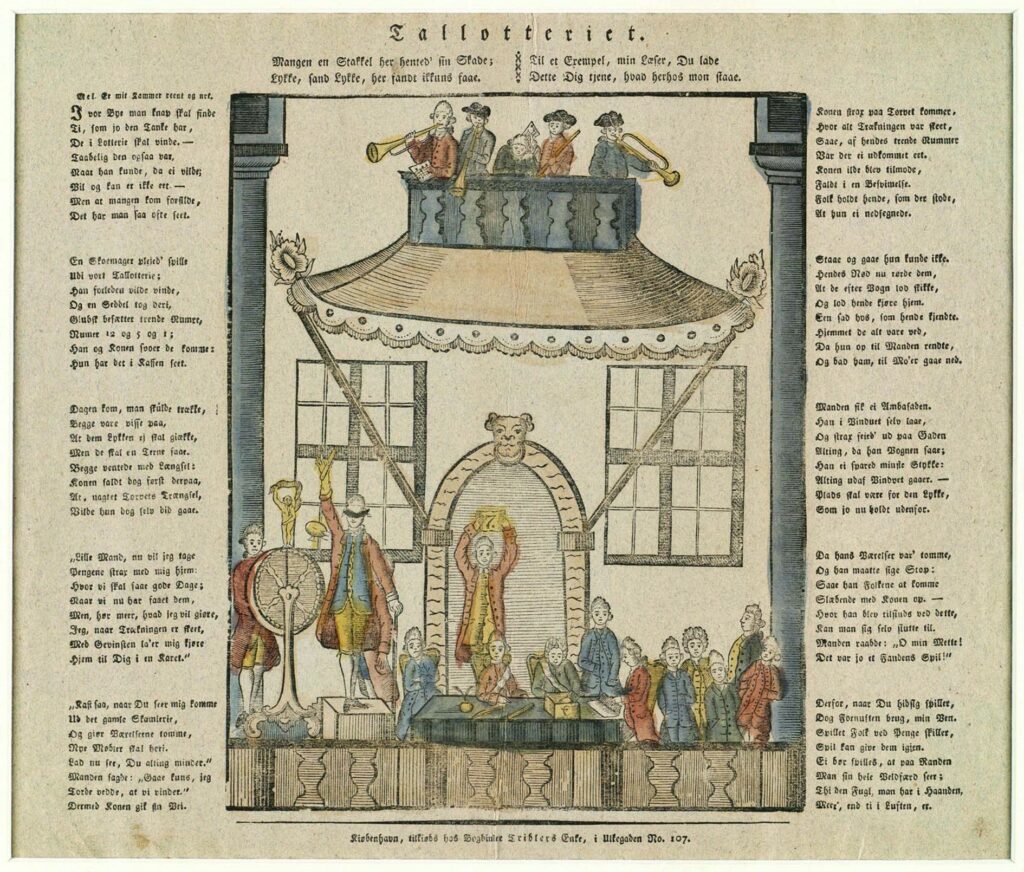

The following literary examples are all taken from Scandinavian literature. We begin in the 18th century, where in several cases we come across what may be called “imaginary lottery winners.” These “winners” share a conviction that they will win the great prize, and this conviction prompts them to enjoy their victory in advance. Two examples are taken from so-called skilling ballads: “En lystig Lotterie-Viise. Synget af een, som havde drømt om Støvle, Kruus, Paryk, Skoe, Og tog derpaa: No.5, 7, 9, 2» (trans. “A cheerful Lottery Song. Sung by someone who had dreamt of Boots, a Mug, a Wig and Shoes, and thereby chose the numbers 5, 7, 9, 2), and “Tallotteriet” (trans. “The Number Lotto”).

In the first of the skilling ballads, we meet a drunkard, who not only drinks, but also treats his fellow drunkards to drinks on credit, convinced that he is about to win the Number lotto. His conviction is attributed to one of the time’s popular “dream books”, providing translations of dreams into winning numbers. The second skilling ballad tells the story of a poor shoemaker who, accompanied by his wife, is convinced that he is going to win the local Number lotto betting on the numbers 12, 5 and 1 – all numbers that the shoemaker’s wife predicted by telling fortunes from her leftover coffee grounds. On the day of the draw, the shoemaker’s wife decides to travel to town to collect their imminent prize. Before leaving, she instructs her husband to clean out their apartment, making room for new furniture, as soon as he sees her returning with the prize in an elegant carriage. As we might foresee, however, their numbers are not drawn, resulting in the shoemaker’s wife passing out and having to be driven home – in a carriage. When the shoemaker sees the carriage, he immediately and unknowingly starts throwing all their belongings out of the window. The comedy of confusion is thereby complete, when the moral is presented: a bird in one’s hand is more worth than ten in the air.

Both of these skilling ballads portraying “imaginary lottery winners” exemplify what John Morreall in Philosophy of Humour (1987) classifies as “superiority” forms of humour. Here, the audience is not only placed “above” the naively duped lottery players but are also provided with information that the hopeful lottery players do not possess. In this regard, the “imaginary lottery winners” recall another comic regular, namely the carnivalesque “king-for-one-day”, where the Dano-Norwegian writer Ludvig Holberg’s comic play Jeppe on the Hill (1723) serves as a prime example of how bad things can get when an ordinary man gets access to great wealth overnight.

Holberg’s Jeppe does not play the lottery, but nevertheless clearly resembles the drunkard from the skilling ballad “Tallotteriet”, when drinking his poor wife’s money at Jacob Shoemaker’s local bar. After Jeppe is drunk out of his senses, he is tricked into believing he is a baron, whereupon he soon assumes the role of a tyrant. In short: Sudden wealth makes Jeppe cruel.

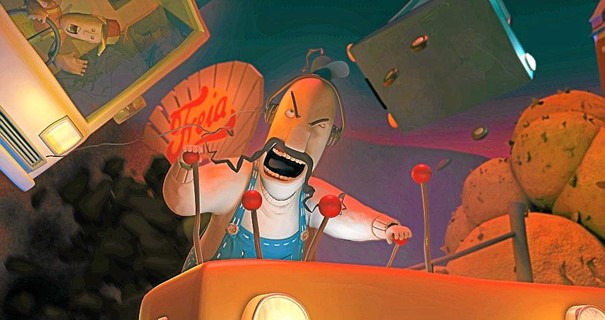

Holberg’s Jeppe is not the only literary protagonist to become cruel when advancing overnight from worker to “VIP”. Here we can make a leap from the humorous “imaginary winners” of the 18th century to children’s and youth literature of our time, where the link between humour and morality remains clear. A title that stands out in this context, is the Norwegian author Erlend Loe’s Kurt blir grusom (trans. Kurt becomes cruel) (1995).

In this book we meet the simple truck driver Kurt, who transforms into a despot after being rewarded a diamond worth 50 million Norwegian kroner. Kurt’s accelerating megalomanic madness is as ridiculous as it is deterrent – or as one of the critics wrote when the book was published: “The moral is clear: Too much money is no good.”

If we return to the lottery motif, while staying in contemporary children’s literature, we can move on to Norwegian author Arnfinn Kolerud’s Snillionen (2017), a title playing with the resemblance between the word “million” and the Norwegian word for being kind: “snill”.

In Snillionen we are introduced to Frank and his mother, who one day win 24 million kroner in the lottery. From being a rather anonymous single mother and son, they all of a sudden become the centre of attention: Everyone in town wants their share in the prize. It does not take long before Frank and his mother realize the negative effect “mammon” has on mankind – an effect Frank’s mother even tries to counteract when promising a “snillion” in reward for good deeds, thereby trying to appeal to the good in man. Snillionen is clearly humoristic; it is a source of laughter – and at the same time conveys a clear moral message, recalling literature from earlier times: Not only does Snillionen demonstrate how stupid one may act when imagining impending wealth; but it also shows how difficult it is to deal with sudden wealth, while at the same time preserve dignity and goodness as a human being. It is easy to laugh. At the same time, literature clearly shows that a lottery prize is not always a joke; on the contrary, it can quickly become serious business.

Written by Inga Henriette Undheim, Associate Professor at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences.

Inga Henriette Undheim

Inga Henriette Undheim is Associate Professor at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. She is an expert in eighteenth-century Dano-Norwegian literature and has also published articles on Norwegian nineteenth-century literature. Her main contribution to the project will be to explore the lottery fantasy in the Scandinavian periodical press and fiction, including children’s literature, as well as providing comparative perspectives on eighteenth-century and contemporary versions of the lottery fantasy in different literary genres.