Responsibility as care: a response and an alternative foundation

The thought-provoking piece posted by my colleagues Tim Dassler and Erik Thorstensen on responsibility as care is an important reminder that attempts at implementing ideals can take us far away from the spirit animating the ideal. I see why an ethos of caring could be a very good thing, yet I have some concerns about using it as a holistic antidote to functional requirements. The first is that it is too vague and too dependent on individual good will and good judgment. While I trust that surgeons care about their patients, I am very happy that they are demanded to have a checklist when operating. The second objection is that their formula “care for what we share” leaves open two big questions: who is included in the “we” and how do we deal with disagreements over what we should care about the most? A common and serious objection to an ethic of care is that it is prone to paternalism, or, as some prefer to say, maternalism. It works where a logic of love is appropriate, but it does not work where conflicts and contestation are endemic: where people care about different things.

In this reply, I will first offer a different interpretation of the paragraph of the EC report “Options for strengthening responsible research and innovation” that they criticise and see as emblematic of the loss of the genuine spirit of RRI. Then I will develop an alternative interpretation of the foundation of the four-dimensional view of RRI proposed by Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten –as you will remember the four dimensions are anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness. This will lead me to propose a different foundation for responsible research and innovation. A foundation that rests on two different legs: (1) distrust of our assumptions and biases, and (2) ownership of our actions. It is the systematic practice of distrust that can lead us to act with confidence.

My colleagues have called us to recover the original spirit of RRI. I am instead emphasizing how long and difficult is the step from good intentions to effective action and lasting achievements.

Somebody likes it functional

So, let me start by repeating the long quotation from the EC report:

“RRI refers to ways of proceeding in Research and Innovation that allow those who initiate and are involved in these processes at an early stage (A) to obtain relevant knowledge on the consequences of the outcomes of their actions and on the range of options open to them and (B) to effectively evaluate both outcomes and options in terms of ethical values (including, but not limited to well-being, justice, equality, privacy, autonomy, safety, security, sustainability, accountability, democracy and efficiency) and (C) to use these considerations (under A and B) as functional requirements for design and development of new research, products and services.“

My colleagues see in this formulation an attempt to commodify responsibility and reducing it to satisfying some indicators. To me this definition stresses the need to carefully consider options and engage in foresight (A), the need to assess possible consequences against a set of ethical values that matter for society (B) and finally it expresses the wish that these concerns become consolidated parts of the process (C). I do not think that my colleagues have problems with the first two points. I believe that where we disagree is in the interpretation of the third. My colleagues clearly dislike the expression “functional requirements” and they see it as an indication that ethical concerns have been turned into some meaningless public management bureaucratic tool.

I must admit that I cannot see what is wrong with functional requirements. Any normative ideal brings with it some requirements, it is not compatible with everything. And should these requirements not be functional? Should they not apply to how things function? Don’t we want the requirements to be practical, applicable, workable? To me this is what functional means. What could be the alternative? Surely, we do not want dysfunctional requirements, do we?

RRI and the limits of good will

To me the appeal to functional requirements expresses a very serious concern, one that is vital also for AFINO. It is the concern for the very difficult step from high minded and lofty ideals to different ways of doing things. Ways that bring ideals into practices and habits of thinking. If foresight and ethical assessment are promoted, it is because they were not happening. At least not enough. This means that actors in the research and innovation chain need to change their ways, their modus operandi.

The great challenge is that RRI asks highly trained and qualified people to do things differently and to do more. This implies pushing them out of their comfort zone, adding further duties, expecting learning and skills building. Perhaps even more seriously, this may interfere with how they interact with their patrons and clients, and with other actors along the research and innovation chain. All this takes time, resources and careful coordination. Unfortunately, all players in the research and innovation chain are already busy and rushing to meet their productivity targets. If, as a famous wit had it, the trouble with socialism was that it would have taken up too many evenings, the trouble with RRI is that it is perceived as taking up too many working hours (and resources).

RRI as constructive disruption

If what I have argued so far is plausible, then RRI aspirations are disruptive, because they imply that things must change. How can this disruption become a constructive disruption? A disruption that does not undermine the functioning of the research and innovation chain? It needs to be incorporated into functional requirements, i.e. requirements that do not prevent the efficient working of the system. But, of course, they should also improve the working of the system. They need to mend the flaws of the system while keeping it running. To me, the EC report appeal to functional requirements has thus a quite positive meaning: it means that aspirations should not be simply nice verbal formulas without a workable counterpart in praxis. Research and innovation should adopt new processes and routines. These should produce some results, some deeds and achievements for which people can be proud and responsible.

Responsibility as mistrust

But what about the disruptive element needed to improve and fulfil the working of the research and innovation chain? If we look at the four-dimensional account of RRI proposed by Stilgoe and colleagues, we can interpret it as articulating a notion of responsibility as distrust in our established ways. If it sounds strange to think of responsibility as distrust, turn the formula around: is it responsible to be overconfident and complacent?

Anticipation is a form of distrust of good intentions and technological optimism. Inclusion is a form of distrust of paternalism and of our ability to understand the needs and aspirations of others. Reflexivity is a form of distrust in our reasons and assumptions, it expresses the need of questioning and being sceptical about our own ways, about what we take for granted. It is an antidote to complacency. Finally, responsiveness is preparedness to change, being willing to resist the temptation of inertia, of doing business as usual. Responsiveness is a commitment to try to take in important feedbacks, to strive to improve and to be prepared to broaden our criteria of what matters and what is desirable.

Responsibility as action ownership

Responsiveness marks the transition to another conception of responsibility, namely responsibility as ownership and confidence. Responsibility as willingness to get the job done and be accountable for the results. Responsibility as ownership responds to the necessity of taking decisions, doing things, and in so doing making mistakes, displease and disappoint people. When we act, we should be aware of the fact that there are risks, uncertainties and moral remainders: that what we have decided to do is not cognitively and ethically unassailable and unimpeachable. And yet we own it. We feel confident enough with it. We stand or fall with what we have decided and done. We accept the risk and go on. We identify with our actions: I am the person who did it.

The two foundations of RRI

My point is that a conception of responsibility that is disruptive in a constructive way, needs to incorporate both responsibility as distrust, and responsibility as ownership. Functional requirements enable a process that starts with responsibility as distrust and culminates in responsibility as ownership.

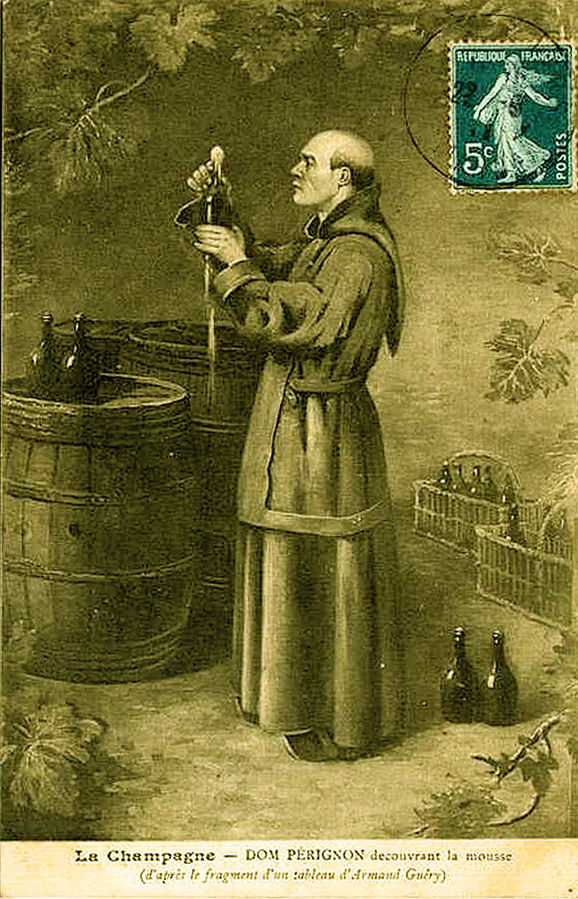

Image from Wikipedia Commons.

To conclude, the foundations of RRI in my opinion lie in a two-stages dialectical process. The first foundation is the practice of distrust towards our good intentions and naïve expectations, towards our ability and prerogative to decide for others, towards our knowledge and assumptions. It is distrust towards scientific and technological hubris. But also distrust in our own vision of the good life.

The second foundation is the courage of ownership, the willingness to act and produce something we are proud to offer to the world. The pride of contribution, when it is coupled with the humility of challenging all our comfortable habits and presuppositions is a good enough foundation for responsible research and innovation. Functional requirements may not sound sexy, just like the rules of the monastic orders seem less inspiring that the life of Jesus. But they were more functional; and who could ignore the enormous inheritance that the monastic orders have left to European civilization?

Featured image: Winston Churchill. From Wikipedia Commons.

Giovanni De Grandis

Giovanni De Grandis has a PhD in Philosophy. In the last ten years he has worked in several transdisciplinary projects and initiatives in the areas of health, new technologies, innovation and public policy. He is the coordinator of the AFINO project and leads Work Package 2.